Features and pitfalls of organizational design efforts

All management challenges are special, but some are more special than others. Organizational design projects, in my experience, are “more special than others” in three important ways.

1. Critical junctures of the organizational life cycle

Organizational design questions often come up at critical junctures of the organizational life cycle. Putting a formal organization in place is a necessity demanded by the rapid growth of maturing enterprises. Often, reorganizations are triggered – and legitimized by – new strategic priorities. The recent reorganization of Google, which set up a holding company “Alphabet” and, through that, more clearly separated internet products from its other technology investments, serves as a case in point.

2. “Building the ship while sailing it”

Organizational re-designs are typically exercises in “building the ship while sailing it”. There is almost never a green field approach in organizing. As a rule, the organization has to keep functioning while changing itself. For example, start-up companies are often “live” before they have had time to systematically think their organization through.

3. “Theoretical” approach based only on analysis and desktop study

Organizational design questions suffer from a purely “theoretical” approach – one based only on analysis and desktop study. A strategic plan may plausibly be based on analysis of and assumptions about market dynamics. Approaching a management structure like this – avoiding real-world testing and the involvement of stakeholders who know how the company really works – can be very risky for the success of reorganization efforts.

These special features explain some of the pitfalls that I have frequently seen plaguing organizational design projects. For example, there is often a disconnect between the strategic plan (usually a more or less consistent piece of analytical effort) and the sometimes messy reality of organizational processes. It doesn’t help that organizational questions are frequently left out of the strategic planning itself. Decisions are often made under time and budget pressure, with the resulting issues later delegated to re-organization and change management exercises.

Work with the Organizational Structure Kit to redesign your organization

One important way to avoid gaps between planning and implementation is to pay careful attention to the organizational design process. We propose that the success of organizational design efforts is as much about the “What”, as it is about the “How” of organizational design.

Balancing the “What” and the “How” of organizational design

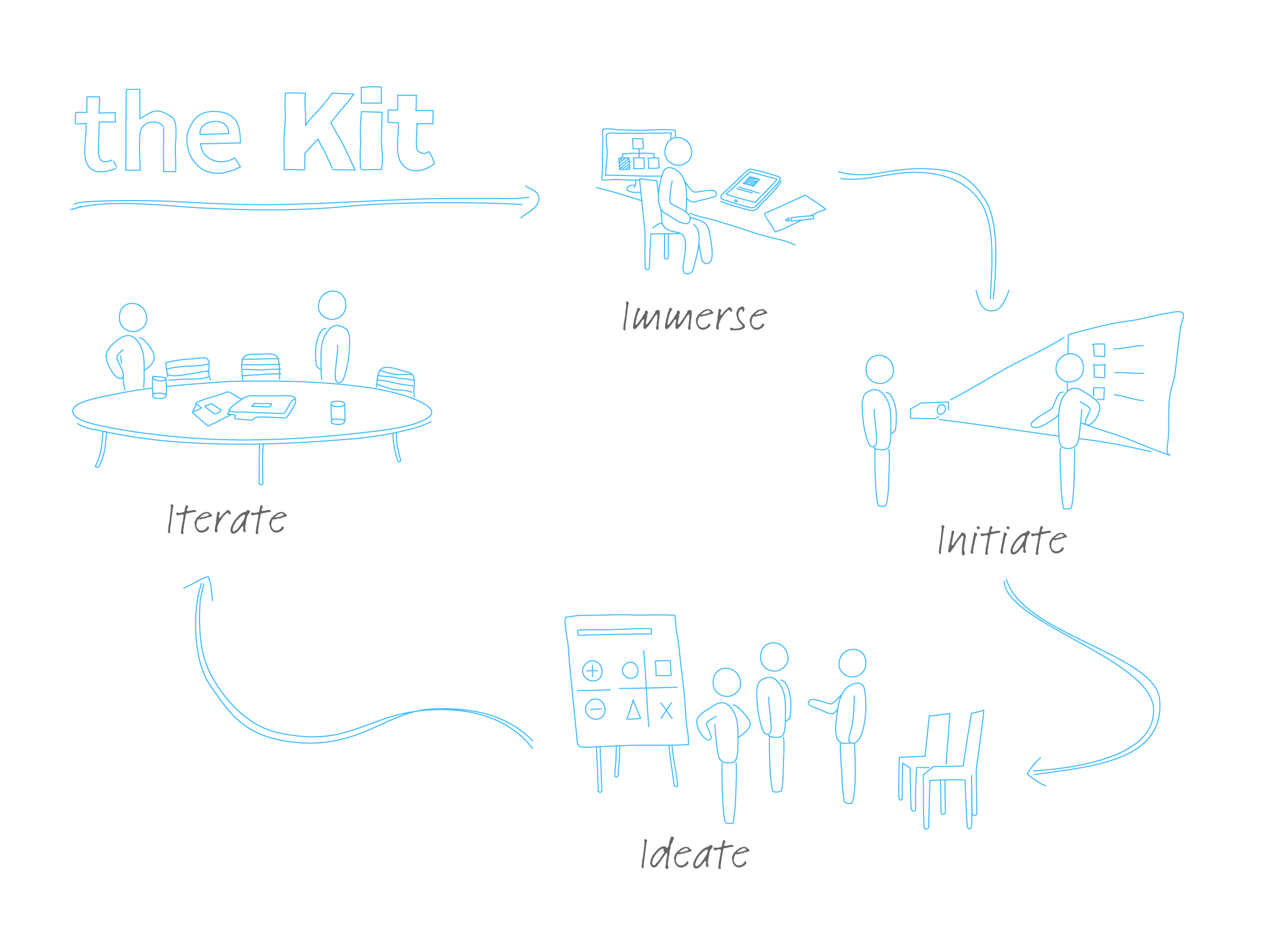

To address the “What” of organizational design, we have developed a framework discussed in our previous blogpost on organizational structure. For the “How” of running organizational design efforts, we have come up with a dedicated process guide that maps the framework to discrete steps, practical and exemplary agendas and specific tools for organizational structure elements. This process can be understood in the four phases depicted below, which are roughly sequential; the steps do, however, invite and allow for re-running “earlier” steps, as the organization learns and the project team refines its approach.

Here are some of the key questions to address in each of these phases:

-

Immerse: What is the framework and model we are working with? What are guiding principles demanded by our strategy, what are limits we have to observe?

-

Initiate: Who are key stakeholders, how do we create a burning platform for our organization design? How do we set up and steer the process?

-

Ideate: How do we come up with key design ideas, how do we ensure consistency between elements, how do prototypes have to look to enable experiencing new management processes and soliciting feedback?

-

Iterate: How can we create test runs, initiate additional iteration loops and create further ideas? How do we prepare decision making and implementation?

The Organizational Structure Kit, whose key component is the process sketched above, contains a framework that addresses key elements of an organizational structure in a holistic manner. It is important to note, however, that the framework, guides and tools do not lead to a deterministic process. On the contrary, organizational design projects invite management innovation and should enable novel approaches marrying best practices to creative solutions and organizational stakeholders’ specific ideas. The Kit is designed to support just that; it provides a solid base to start the process, raises key questions and shares essential knowledge to enable productive discussions leading to creative and compelling answers.

A number of deliberate choices can support the customizing of the organizational design approach

First, organizational structure should be strongly linked to, and derived from, strategy. This strategy usually needs to be translated and specified for different functions, geographical units or levels of the organization. For example, a former client – global head of a corporate function – facing a major group-wide corporate restructuring, used it as an opportunity to develop the functional agenda and organization. Switching from a reactive to a proactive mode, he led his team to come up with an innovative functional operating model and organizational unit structure in line with the new strategy. A focused and customized unit-level approach toward organizational structure allowed him to integrate functional priorities with the broader strategic agenda, for example by re-thinking the interfaces and delivery mode of his function with the broader organization.

In addition, some elements of an organizational structure may be more, or less, relevant in specific settings. Depending on strategic objectives and the baseline, one may want to focus more on some elements than others (for example, cooperation across units may be a more pressing issue than changing the hierarchical structure of spans and layers).

Paying careful attention to the organizational design process is one of the best change management approaches there is. An often-quoted (and much-adapted) proverb in change management says that people do not resist change – but they resist being changed (the original is usually attributed to Peter Senge).

Making sure that the process of organizational design addresses critical trade-offs, reflects the best thinking and has a proactive approach to iterations and testing significantly increases the chances of acceptance and ownership for team members who have to make the organizational structure successful on a day-to-day basis.