Organizations that seek to stay viable for the long term must build and retain their capability for change. This change can follow two patterns: classical organizational models require intensive peak change episodes. Novel approaches to organizing allow for continuous decentralized change across the organization.

There is much talk these days about how 20th-century corporate structures built to exploit stable business models are not fit to enable the constant generation of new ideas, nor are they capable of facing disruptive change.

At the same time, any effort aimed at exploring the unknown and facilitating change in the economy at large requires organizations: systems designed to solve complex problems in a collaborative way that results in a collective output larger than the sum of its parts.

The question then is how to set up management structures that are able to adapt to, or even anticipate, sudden, massive changes in the organizational environment. How can you design and work in and on your organization to allow it to adapt to the outside when business moves quickly?

The Jack Welch equation: the effects of internal and external change

Jack Welch summarized this challenge nicely when he said that

“when the rate of change inside an institution becomes slower than the rate of change outside, the end is in sight”.

Welch essentially formulated a principle of systems thinking. For a system to survive, it must change in accordance with its environment, insofar as it depends on that environment for its functioning. In an open market economy, this comes down to the question, simply put, of whether a firm can attract sufficient capital inflows.

Two possible patterns towards permanent change: a series of peak change episodes vs. continuous adaptation

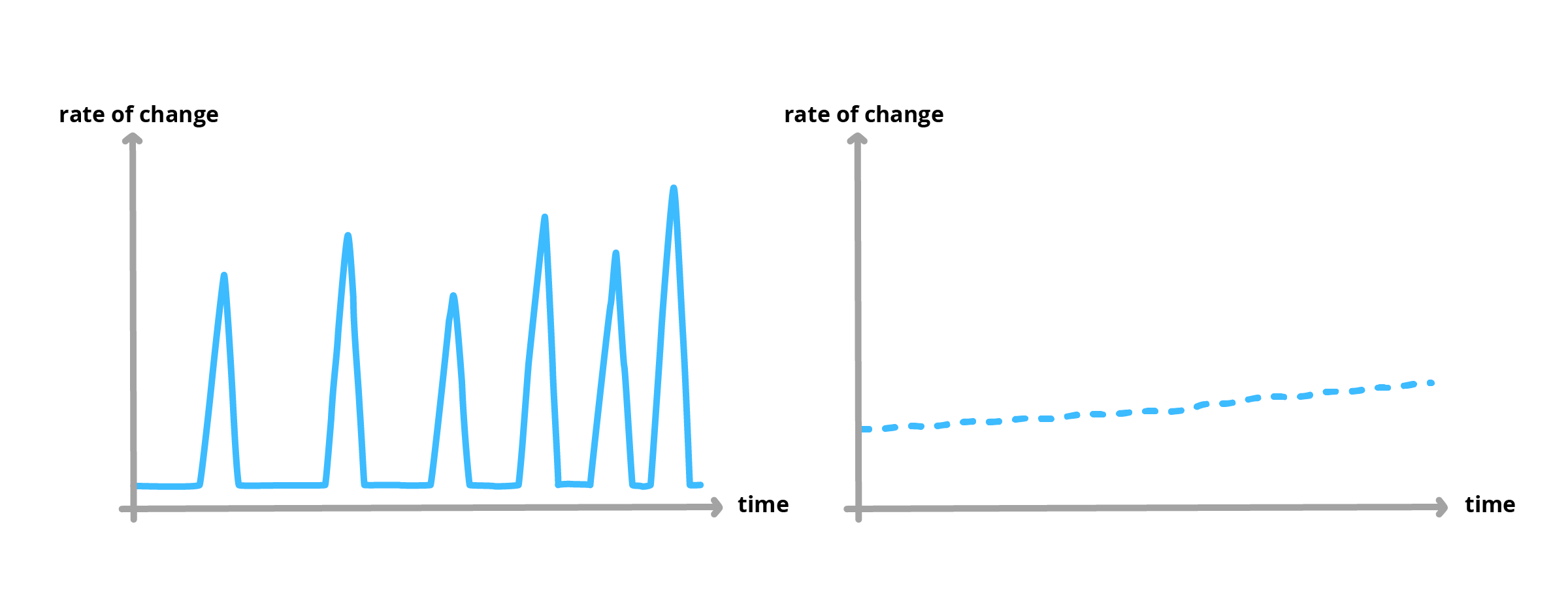

Now, in principle, there are two different ways to bring about this internal change that Jack Welch described: an approach with frequent “peak change” episodes, and another approach based on continuous adaptation.

-

In the first mode of organizational change, peak change, you restructure the whole organization any time you come close to par in the Welch Equation of internal and external change. This is a pattern very familiar to many large corporate structures. Restructurings are followed by change initiatives, and ever shorter phases of “freezing” target states, before the next major change effort takes place.

-

In a second mode of organizational change, continuous adaptation, you substitute this step-wise change with an approach in which you constantly adapt in micro-steps to a changing environment. You keep up an average rate of change that allows you to constantly stay ahead of outside developments – instead of alternating between high speed and full stop.

Ending the rollercoaster ride of peak change and artificial stability: jumping on the continuous change curve

Being able to jump on this continuous change curve may sound attractive to many:

-

The “great leaps forward” of peak change often involve massive efforts, which take time, money, and energy away from delivering an organization’s core functions.

-

Moreover, the implicit and frequently broken promise that the next re-org will finally get it right is tiring for managers and employees.

-

The “future of work” for many seems to be embodied by endless major reorganizations.

For argument’s sake, I’ll continue to adhere to this (admittedly very pointed) distinction to describe approaches to organizing for each of the respective change modes – which in turn translate into specific challenges for the organization designer.

Two patterns of change: successions of peak change episodes and phases of stability (left) and continuous adaptation (right)

The standard narrative today is that a permanent succession of “peak change” episodes, as shown on the left-hand side of the graphic above, is bad, and the right-hand side, demonstrating continuous adaptation, is (or would be) awesome.

The only problem is that we have a much greater body of management knowledge on how to drive the left-hand sort of “peak” change. The right-hand side of continuous adaptation represents more of a search than a field of proven best practices. Recent management innovations under the banners of agile organizing, responsive organizations, and Holacracy are still in experimentation mode, although they are yielding valuable experiences, insights, and data.

This experimentation is needed and it’s valuable. However, I would dare to propose that org designers will always have both sides of this coin.

Reality is and will remain mixed: micro and continuous self-organizing will always happen regardless of how formalized the set-up of an organization is. And some central, top-down design decisions will always be part of a designer’s repertoire, for reasons of scale, operational reliability, or to fulfill non-negotiable outside requirements, such as legal and regulatory duties.

The big question then, of course, is: “how” – how to move closer to the right-hand side and at the same time balance approaches to keep an organization reliable and adaptable.

Get an overview of our tools and frameworks to build powerful organizations.