Can design thinking promote organizational responsiveness? I believe the answer is yes. Yet the interesting part is the process of getting to that answer and exploring the implications for new forms of organizing. To that end, it makes sense to first define “design”, propose several working principles associated with design thinking, and then contrast those principles with some characteristics we expect responsive organizations to have. The conclusions are preliminary and ideally they spark further ideas and debate (which you are invited to join by using the comments box below or by dropping us a note via email).

Here’s why this topic interests us so much: the hypothesis that there is something to be learned in considering management a design activity is one of the main intellectual roots of Management Kits. (And while we’re talking about our roots, we also count the management innovation debate and an action-learning approach towards management development among the key ideas guiding our work here at Management Kits.)

Defining design and design thinking

In exploring the affinities between organizational responsiveness and design thinking, I rely on a classical definition for design from Herbert Simon:

“Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones. … Design … is concerned [not with how things are, but] with how things ought to be, with devising artifacts to attain goals.”*

In line with this definition, organizations and artifacts resulting from management work are outputs of a design activity. Organizations and management models are designs and managing is therefore – or to a large part can be viewed as – designing.

I emphasize this point because a common understanding of design thinking associates it rather narrowly with methodologies to come up with products and services. The classical model of design thinking as promoted by IDEO, however, does not in any way necessitate such a narrow understanding. In this model, design thinking seeks to balance the desirability, viability, and feasibility of designs, while starting out from the perspective of human desirability (hence the discussion of human-centered design).

Source: IDEO (2015): The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design, p14

Design thinking – some working principles

I propose that there are seven common working principles in design thinking. This selection of principles and their understanding is derived from my own research and practice. And while this list is hardly at odds with the mainstream and the (unwritten) canon of design thinking, my take is surely influenced by my interest in exploring the relevance of the broader approach for management.

1. Empathy with users. Design thinking generally requires designers to “step into other peoples’ shoes”. There are tons of pertinent examples for how this attitude and practice can improve the creation of products and services. With our specific interest in mind, this raises the question of who the “user” is when it comes to management processes or organizational artifacts. (We will save our answer for another blog post, so stay tuned!)

2. Working through visuals. Broadly understood, this principle means the expansion of reasoning beyond technical language and data to include images and stories. The prompt “Show, don’t tell” captures this principle rather well, originally describing a writing technique used “to allow the reader to experience the story through action, words, thoughts, senses, and feelings rather than through the author's exposition, summarization, and description”.

3. A discipline of prototyping, meaning the principle to move beyond concepts or models early in the process and make deliverables and suggestions as tangible as possible. Sometimes this is formulated in the drastic imperative “Demo or die” (for buffs like me who are into the history of jargon, check out these two blog posts exploring the origin of the phrase at MIT’s Media Lab and how it influenced early agile development).

4. Tolerance for failure and learning from failure. The connection between exploring, failing, and learning is neatly encapsulated in the proverb “Nothing is a mistake. There’s no win and no fail, there’s only make.” Originally devised as a classroom principle, it is often quoted and rightly so. At the same time, business often makes for a different context than the classroom, and learning to fail productively in management roles is easier said than done. For a helpful differentiation of “failures”, consider this HBR piece by Amy Edmondson on strategies for learning from failure.

5. Embrace ambiguity and trust the process. Quick decisions and decisive execution are mantras in the business world – and consequently decision processes are often perceived as being too slow. Ambiguity is a fact of organizational life as much as clarity of decision power and clear accountabilities are the goals. Against this background, the suggestion to “explore lots of different possibilities” may not seem very attractive at first. However, it expresses the imperatives not to: settle for the first best idea; simply do (and rationalize) what the boss thinks is best (also known as HiPPO patterns, where people by default defer to the “Highest Paid Person’s Opinion”); or go for some “benchmark” and “best practice” of questionable validity and relevance. We suggest that a self-conscious creative confidence supports a design-thinking attitude in the face of management challenges. And trusting the process also means having a deliberate and disciplined approach towards the design process, which is not the same as pushing through a plan in the form of a predefined sequence of action steps and milestones.

6. Iterate, iterate, iterate. Our professional culture by default demands a “first time right” approach with regard to many practices and procedures. It seems to lie at the core of our professional selves that we are selected and paid for doing things the right way (and that we are trained accordingly and exhibit the right experience to prove it). For the most part there are good reasons for it. But the downside is an inbuilt structural conservatism when it comes to many fields of innovation, simply because the first idea will seldom be the best. Not doing it again will prohibit learnings between iterations. In the words of the IDEO Field Guide to Human-Centered Design: “We iterate because it allows us to keep learning. Instead of hiding out in our workshops, betting that an idea, product, or service will be a hit, we quickly get out in the world and let the people we’re designing for be our guides.”

Asking for iterations may not come naturally to many in out-of-design contexts. It will also depend on the facilitation of the process to make room for such loops.

7. Collaboration and spaces. Design thinking typically demands more than an open space office (which is often a measure for maximizing utilization of costly floor space compounded by a superficial understanding of productive communication patterns within teams). Instead it requires a flexible space that can be rearranged according to the working needs of the respective teams and their members, in different phases and episodes of the process. This is due to the deeply collaborative nature of work – either between contributors or between designers and users in the course of co-creation. Creating a flexible, accommodating space conducive to collaborative exploration and learning is also about breaking out of a pattern once described by Winston Churchill: “First we shape our buildings, then our buildings shape us.”

Now, can a pattern of management work geared towards these principles promote organizational responsiveness?

Responsive organizations

“Organizational responsiveness” has become one of the various labels used to describe efforts to define new approaches to managing and organizing. Some principles are neatly, if at a somewhat high level, described in the Responsive Org Manifesto. This proposes that there are five tensions that must be balanced in order to build and lead organizations able to thrive in less predictable environments. The five tensions are:

A. Profit – Purpose

B. Hierarchies – Networks

C. Controlling – Empowering

D. Planning – Experimentation

E. Privacy – Transparency

In general, the manifesto proposes a shift more to the right in order to accomplish a responsive organizational profile. For example, with regard to the third tension (Controlling – Empowering), the manifesto states that “rather than controlling through process and hierarchy, you achieve better results by inspiring and empowering people at the edges to pursue the work as they see fit – strategically, structurally, and tactically.”

Leveraging design thinking for organizational responsiveness

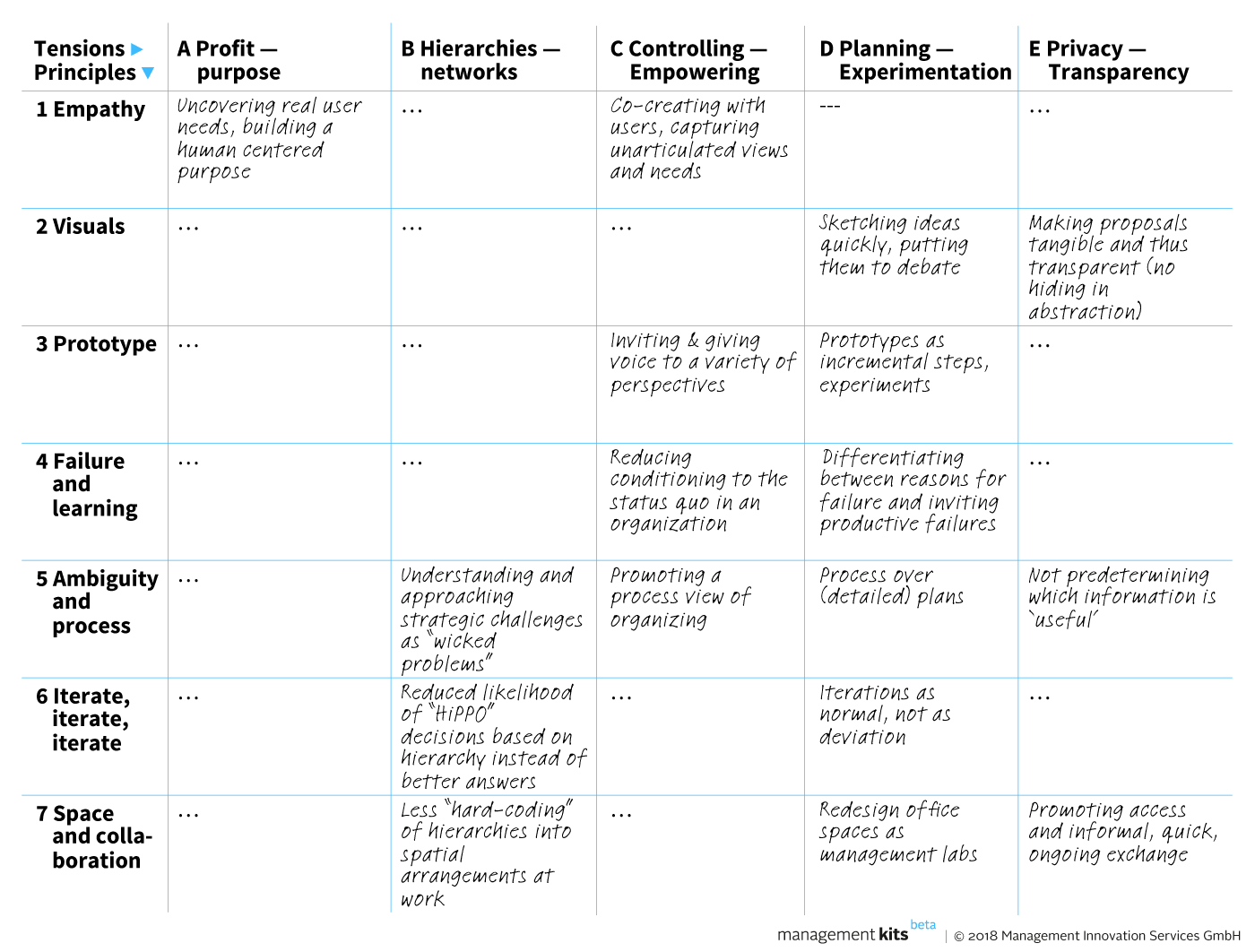

The matrix below juxtaposes the seven design-thinking principles on the left-hand side with the five tensions on the top. Each intersection then raises the question: could this design thinking way of working help find a more responsive balance to the tension? For example: could the principle of empathy, the idea of stepping into other peoples’ shoes, move organizations away from an overly exclusive orientation towards profit, and towards an increased orientation towards purpose? The notes in the table indicate a preliminary answer for the respective intersection of principle Y and tension X.

My goal is not to comment on every field of this matrix. Clearly some intersections seem less relevant than others, at first sight at least. In any case, the matrix is supposed to be a thinking device and methodological scaffold. Here are some insights I think can be drawn from the juxtaposition within the matrix.

Source: Management Kits (2018). Contrasting common design-thinking working principles with the tensions that need to be balanced in order to achieve greater organizational responsiveness.

-

First, and perhaps most obviously, an orientation towards experimentation over planning (tension D) proposed by the manifesto is very much in line with the design-thinking principles. A work process committed to those principles should promote responsiveness by making experimentation more likely to succeed, and by making people in charge of that experimentation more comfortable giving up the apparent certainty provided by a neat plan.

With the other four tensions the case for design-thinking methodologies is probably less straightforward, although there are working principles relevant for all of them.

-

Shift from profit to purpose (tension A)

In principle, design thinking as a methodology to create products and services could serve any organizational goal. However, we would expect that a consequential user centricity (principle 1) will lead to a more holistic understanding of the organization’s value creation and goals. We would expect a consequential user centricity to put a purely technological rationality or a purely economic rationality into perspective. And we would expect this user centricity to create a space where organizational stakeholders can make sense of the actual purpose and value of the organization’s pursuits, framing “profit as a by-product of success” while aiming “to do well by doing good” (in the words of the manifesto). It goes without saying that empathy for the user is not the only factor that can promote an increased focus on purpose, but it speaks to the contribution that design thinking can have for increased responsiveness. -

Seeking a new balance away from hierarchies moving towards networks (tension B)

The manifesto states that “technology and connectivity has increased our ability to self-organize, collaborating more easily across internal and external organizational boundaries. It is no longer necessarily true that coordinating through a Manager is more effective than people self-organizing.” Nevertheless, the manager-to-subordinate reporting relationship is still one of the primary building blocks of modern organizations, not least because of some clear functional advantages of this arrangement for the division of labor at scale. In addition, it is probably hard, although becoming less so given the increased variety of organizational experiments, to imagine alternatives. I propose that some of the design-thinking working principles tend to suspend hierarchies. For example, embracing ambiguity and trusting the process puts formal leaders and teams into the same spot, as they are both confronted with an open design challenge (which could be a new strategy or a new organization design, for example). There is no reasonable expectation that the manager should be able to solve the issue on his own, because of his superior expertise or experience (principle 5). A focus on iterations and the related learnings on a previously unexplored challenge also makes pre-given knowledge and power less relevant, as the knowledge created stems from the work process in the first place. Even more so, the process de-legitimizes any structural power-holder from claiming to have a predetermined claim to the right answer (principle 6). And finally, the emphasis on open and flexible spaces to support collaboration (principle 7) prevents the spatial codification of hierarchies (e.g. via seating arrangements, corner offices or other regalia of corporate power irrelevant to the design process). Of course, the success of the very process hinges on the quality of the facilitation as well as other factors, such as the level of support found in the organizational context. -

From controlling to empowering (tension C)

Design-thinking methodologies can be seen to empower organizational stakeholders in a variety of ways. These include: giving a voice to users in the first place and allowing them to contribute their ideas and reactions, even if it means that preconceived plans lose value and relevance (principle 1); inviting feedback and experiences based on tangible prototypes (principle 3); reducing the tendency to confirm the status quo by opening the discourse for explorative failure (principle 4); and promoting a process view of organizing, which per se eludes a static understanding of control within organizations (principle 5). -

The shift towards increased transparency (tension E)

In discussing this tension, the manifesto emphasizes the ubiquitous availability of information, de-valuing “information as the currency of power: hard to come by and hard to spread”. Focusing on design-thinking principles, another, equally important aspect comes into view, namely that information and knowledge are the very outcome of the work process itself. The knowledge emanating from the design team is neither easily accessible nor guarded by those in power. It emerges through collaborative exploration, iterations, and testing, and thus makes transparent what was initially hidden from sight. The results of user tests, deep customers interviews, observations, prototypes in action and iterations, as guided by a design challenge, is knowledge creating. Trying to hide and control parts of that process decreases its value as an explorative device. In this sense, working in designerly ways can support managers in more productive information sharing and communication practices, and in turn support an increased organizational responsiveness. Principles 2, 5 and 7 seem most pertinent in this respect.

***

As mentioned in the beginning, the conclusions presented here are preliminary and meant to contribute to further ideas and debate. In any case, the logic behind the approach informs how we research, design and deploy resources at Management Kits: for example, by developing original canvas formats that are based on key findings from management research (see the canvases on organizational structure, high-performing teams, and leadership development), or by building process guides and agendas that support setting up and driving a collaborative design process.

There is a bunch of free resources for anyone interested in the approach that can be found here:

Note: This blog post builds on a talk I gave at the Responsive Org Meetup Zürich and the ensuing discussion.

* Herbert Simon (1969): The Sciences of the Artificial, Cambridge (Mass.), p 4, 111.